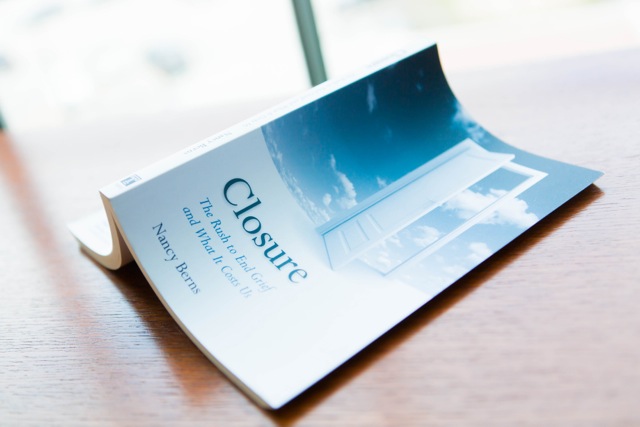

The first major 9/11 public memorial was dedicated in front of the Pentagon on September 11, 2008. The day after the memorial opened, The Washington Post ran a story titled “A long-awaited opening, bringing closure to many.” After the death of Osama bin Laden in May of this year, headlines around the nation proclaimed that we could now have closure. And the tenth anniversary of 9/11 will not only bring significant memorial services and poignant reflections, but also more declarations that closure has arrived. But if you have been following the same events closely, you will have noticed other voices—none louder than family members of 9/11 victims—telling people that there is no closure.

Those grieving for loved ones killed in the attacks of September 11, 2001, continue to encounter public commentary about when or how they should find closure. However, those asserting a need for closure typically do not stop to question what this concept means, whether it exists, or if those hurting even want closure.

Closure has become a new emotion for explaining what we need and how to respond after trauma and loss. It is not that people are experiencing some feelings that were never felt before, but rather closure is a new way of talking about emotions that follow a loss. But closure is not some natural emotional state that we can simply find. Rather, it is a rhetorical concept. Any understanding we have of closure comes from how people have defined it through stories, arguments, court cases, and so on. And there is no agreement as to what closure means. People talk about closure when describing a range of disparate ideas, including justice, peace, healing, and acceptance. But it is also used to describe contrasting notions like forgetting and remembering not to mention forgiving and getting revenge.

Although definitions vary, the most common interpretation of closure is a satisfying end to some traumatic event. Closure echoes finality—the act of closing a door. When grieving loved ones hear the word, many interpret it as the ending of a life, love, and relationship. Knowing this, it is easier to see why some say, “I hate closure.” or “I do not want closure.” They want to remember their loved ones.

One of the concerns with the rush to proclaim closure after a particular memorial service, the identification of human remains, or after the death of Osama bin Laden is that it fails to reflect the grief and loss that many experience. The pain of grief does lighten over time but people continue to feel the loss. People learn to integrate a loss into their lives but they do not close the door on love and memories.

By getting beyond the talk of closure, we can give people more freedom to grieve. In order to lessen the rush to find closure, we need to understand that it is possible to hold joy and grief together. We can learn to live life again without “closing grief.” Talking about tragedy and grief without the expectations of closure respects pain while offering hope.

The attacks of September 11, 2001 are not a Hollywood movie in search of a tidy feel-good ending. It is true that many people will watch television specials or news coverage of 9/11 events and then walk away already absorbed in other thoughts before the credits roll. Nevertheless, it is worth remembering that memorial services do not end grief, but hopefully they do acknowledge loss and help us reflect on larger lessons incurred from this tragedy.

Leave a Reply